3D in Geospatial: NeRFs, Gaussian Splatting, and Spatial Computing

Neural radiance fields and Gaussian splatting provide new ways to create 3D replicas. In this post I explore how they relate to traditional methods such as photogrammetry and 3D engines, their relationship to geospatial, and what applications we might see them in.

Two standard ways for building 3D replicas are with photogrammetry or with a 3D development engine. Photogrammetry derives a 3D representation from a set of images of the site. The workflow typically uses a structure-from-motion algorithm to determine camera poses (location and orientation from which the photos were taken), then multi-view stereo to create a dense point-cloud, from which you develop a surface reconstruction. Using a 3D engine is conceptually the reverse of photogrammetry. You start with a blank scene and add in all the elements to approximate the real world. This allows you to replicate not only what currently exists, but also imagined past and future states.

Neural radiance fields (NeRF) and Gaussian splatting are recent techniques which add to our repertoire of tools to make 3D replicas. Both are similar to photogrammetry in that they are data-driven and reconstruct a scene based on images. First introduced in 2020 and 2023 respectively, they’ve rapidly grown in popularity – apps like Polycam enable anyone to make a 3D scan and post it online. Both these techniques present novel solutions to the problems of inverse rendering (estimating physical attributes of a scene) and real-time novel-view synthesis (generating new images of the scene).

Neural Radiance Fields

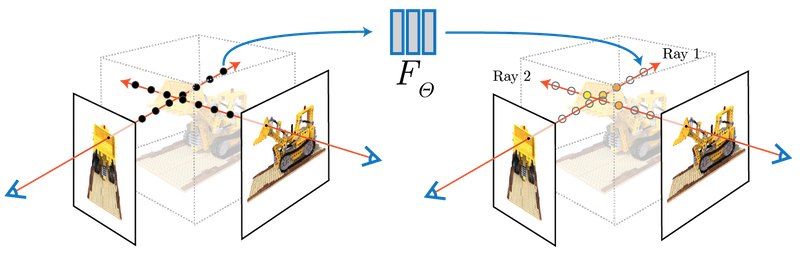

NeRFs represent 3D scenes using a neural network, rather than an underlying mesh or point cloud. The inputs to the neural network are spatial location \((x,y,z)\) and viewing direction \((\theta, \phi)\). The outputs are volume density \((\sigma)\) and emitted radiance \((R,G,B)\). To synthesize a view, points sampled along camera rays are input to the neural network and an image is generated from the outputs using volume rendering techniques. The network learns to represent the scene from a set of training images and camera poses, and is optimized using gradient descent. Once trained, new views are synthesized by repeating the process of querying points along the camera ray and rendering the output of the network.

Gaussian Splatting

Gaussian splatting represents 3D scenes similar to point clouds. Points are extended to have a 3D Gaussian distribution in space, opacity (so translucent objects can be represented and for composition of overlapping Gaussians), and spherical harmonics (allowing points to change color as view direction changes). These modifications make Gaussian splats more expressive and better able to reconstruct scenes. Points essentially become ellipsoids with learnable size, orientation, and visual appearance.

An initial (maybe surprising!) observation is that Gaussians can be arranged such that they form an excellent representation of an image. Efficiently going from 3D Gaussian splats to a 2D image for a given camera pose is enabled by a differentiable renderer. The differentiable part is key, because it allows using gradient descent for optimization in tandem with heuristics for adding, splitting, and removing existing Gaussians.

Understanding these Methods

The process of generating a NeRF or Gaussian splat begins from the same point. Both require a set of input images and camera poses. As in many data-driven applications, the data quality is a key determinant of how good the output is. Motion, changing light conditions, and glare in the images all have detrimental effects on the output. The path of the camera through the scene is important. Given a video or set of images, Colmap is the standard open source software for determining camera poses. A detailed discussion on effective image capture can be found here.

At the core of both NeRFs and Gaussian splatting is differential rendering and optimization with gradient descent. The optimization of the multi-layer perceptron used in NeRFs is in-line with training performed on most neural networks. Gaussian splatting interleaves gradient descent with heuristics on adding, splitting, and removing Gaussians. Attributes like location, color, and size are optimized with gradient descent, while the number of Gaussians is adjusted periodically. Although Gaussian splatting can converge from a random point initialization, the sparse point cloud created as a by-product of determining camera poses is often used for initialization.

There’s a lot of active research on NeRFs and Gaussian splatting. Often concepts from one can be applied to other (such as using diffusion models as priors). As in many AI fields, progress is driven by both academia and industry. Familiar names like Nvidia, Google, Meta, as well as less familiar ones such as Niantic (makers of Pokemon Go) are all involved in advancing these methods. Lots of exciting papers are coming out on:

- Scaling the methods for training and navigating extremely large areas

- Improving fidelity of reconstructions

- Incorporating generative AI to create new scenes and as priors

NeRFs and Gaussian spattling aren’t without their challenges. They can suffer from ‘floaters’ (bits of the scene that appear floating in space), flat textureless surfaces can be challenging to capture convincingly, and mirrors and windows are often hazy. Georeferencing models and accurate dimensional scaling still require control points.The quality of outputs is highly dependent on both the input data (sharp photos with significant overlap between images) and camera pose estimation. No escape from the concept of garbage in, garbage out.

A key distinction of photogrammetry from NeRFs and Gaussian splatting is that a lot is known about the accuracy of the output model (it’s used by land surveyors to determine legal boundaries). A rule of thumb is that the positional accuracy using photogrammetry is between 2 and three times the Ground Sampling Distance. There’s no equivalent for NeRFs or Gaussian splatting, nor a deep body of research into the subject. Even defining the surface for NeRFs and Gaussian splatting is ambiguous, since their definitions are fuzzy.

In practical terms, both NeRFs and Gaussian splatting can produce excellent visual results. There’s multiple open source implementations, including Nerfstudio which implements both methods and is released under the Apache 2.0 license. Meshes can be extracted from both NeRFs and Gaussian splatting, and both can be exported to applications such as Unreal Engine. Interoperability with other applications is on an upwards trajectory.

From a geospatial perspective, Gaussian splatting may have an edge due to its similarity to point clouds. Indeed, Gaussian splats can be exported as point clouds (and back again). One advantage of this is that they can be manipulated in familiar tools like CloudCompare. A second advantage is that point cloud data from LiDAR provides a natural initialization point for Gaussian splatting.

Relation to Geospatial

NeRFs and Gaussian splatting build on the possibilities of photogrammetry. I suspect a lot of similar discussion around use-cases and applications taking place now focused on NeRFs and Gaussian splatting also happened previously in the context of photogrammetry. My thought process on this subject inevitably reflects that NeRFs and Gaussian splatting are my entry point into exploring the intersection of geospatial and 3D. I’m optimistic that these methods will have interesting implications, and lead to new products and ventures.

NeRFs and Gaussian splatting intersect with trends in other technologies. On the data collection side, drones have become extremely capable and relatively affordable. Similarly, video and photo quality from modern cell phones is excellent (although worth bearing in mind there is significant post-processing). LiDAR from the iPhone provides positional accuracy on the centimeter scale. While consumer technology doesn’t match professional equipment, it does have the advantage of being widely available and easy to iterate with. It’s also worth noting the trend of open data, with jurisdictions like British Columbia collecting and releasing a LiDAR scan of the entire province (which can be used to initialize or constrain 3D models).

The emergence of VR headsets (e.g. Meta Quest 2 and 3 or Apple Vision Pro) provides a natural interface into 3D. Visualizations made with NeRFs and Gaussian splats on these devices can be quite convincing, and are well suited for the successful geospatial VR use-cases I’ve encountered: collaborative remote site visits, classroom safety training about site hazards, and public engagement around remediation work.

The adoption of NeRFs and Gaussian splatting may catalyze new connections in the geospatial community. AI has been taken on board by geospatial, and applied across the board from weather modeling to analysis of satellite imagery. My impression of photogrammetry is that of a separate world, dominated by proprietary software and specialized methodologies (admittedly, this is based on limited evidence). However, both the methods underpinning NeRFs and Gaussian splatting, as well as the software tools (Python, PyTorch, Cuda), are familiar and accessible for folks experienced in deep learning. This can serve as a bridge and facilitate more conversations between folks involved in AI and 3D.

There’s increasing use of 3D in the geospatial world, largely driven by advancements in LiDAR and Photogrammetry. Working in 3D can be advantageous for numerous locations and phenomena: mines, industrial facilities and structures, landslides, avalanche terrain, geological mapping. The vertical dimension is foundational to all these examples. There’s no reason to think 2D is obsolete, but these technologies remove barriers to working in 3D, such that the choice best reflects the underlying problem rather than software constraints.

A crucial question in the geospatial context is what problem do 3D immersive replicas solve? A framework for exploring this question can be borrowed from earth observation. In satellite imagery, the discussion is often centered on the hierarchy of mapping, monitoring, modelling and managing, with increasing value as you move towards the right. (other formulations of this framework exist, and it’s worth noting it parallels the analytics maturity framework used in data science). The main point is ultimately we want this technology to enable better decisions.

The combination of 3D with the underlying data is an interesting space

3D enables using space as an index into information. Most NeRFs and Gaussian splats are derived from videos, from which a set of frames are extracted. In the case of a video, the index we navigate with is time. For a set of frames it is the position of the filename relative to others (typically these are frame_0001, frame_0002, etc). You have to scroll in a desktop window or navigate by name in a terminal. With a 3D representation, the index becomes the location in the 3D replica, which is a more natural interface. So if you want to see all the images of a particular place, you can navigate there spatially, and bring up the closest images.

The 3D model is a summary of the data. Although 3D replicas aren’t quite photorealistic, they can help you determine where to take a closer look. A hypothetical use-case may be a forward-looking video from a train along a route where vegetation encroaching onto the tracks is an issue. Turning the video into a 3D immersive scene allows you to immediately access the parts of the route which are of interest, and examination of the 3D replica can help determine areas of concern and quickly access the ground truth images. Information from underlying image analysis with computer vision can also be easily incorporated. The 3D replica is a tool both for detailed analysis, but also for communication between stakeholders.

Effective Storytelling

3D in of itself can be an effective story-telling tool. This is reflected by the concept of VR as the “ultimate empathy machines”, based on the idea that it gives users a sense of being there. NeRFs and Gaussian splatting can be very effective in conveying this sense of being on location – both on a headset or other device. The use-cases where I’ve seen VR/3D be extremely effective centre on public engagement. In one case, headsets allowed the public to follow infrastructure development to clean water in a polluted site inaccessible to the public due to the safety concerns. Another was site restoration, where engineers recreated the site as they envisioned it after reclamation was completed. In either case, no one in the public wanted a 200 page report. Building a 3D replica helped shift the conversation to story-telling, and more intuitive ways of understanding the work being done (rather than then a report or set of slides).

Specific Applications

Two specific applications I’m particularly excited about are Digital Twins and Workplace Safety and Training.

Digital Twins are virtual representations of physical objects or systems. They extend 3D visualization by incorporating real-time sensor data from the object to allow for things like optimizing performance, predictive maintenance, and diagnostics. Although a lot of the complexity is on the underlying data side, the visualization remains important. For digital twins of real-world environments, NeRFs and Gaussian splatting offer excellent visual representation. Given the strong focus around these technologies on creating visualizations with consumer technology, they provide a route for continuous field data collection to update the system.

An adjacent use-case to digital twins is spatial-asset management. Considering capturing a facility with NeRFs or Gaussian splatting, and then labelling components within the visualization. Each 3D entity can have a unique id, which is then associated with records, documentation, and maintenance of the system. This can be used to communicate about work that needs to be done. For instance, a visualization can be sent to a service provider ahead of time, with the location of relevant items marked on the visualization. Such an approach would also help with remote maintenance support.

Workplace safety and training is important across numerous industries such as mining, construction, and energy. There’s significant advantages to training in 3D (and optionally in VR). Situations where working with a NeRFs or Gaussian splat 3D replica would be advantageous include:

- Hard-to-access sites, such as remote or confined spaces.

- Training around specific hazards found at a site.

- Onboarding without interfering with operations.

- Familiarizing employees with site modifications.

Conclusion

NeRFs and Gaussian splatting add to our repertoire of methods to create immersive 3D replicas. Matched with careful data collection, they create highly realistic scenes navigable in real-time like a video game. Load these onto a VR headset and the output is stunning. For applications where precise geometries are crucial, photogrammetry will still remain standard.

Both the underlying methodology and codebase are relatively accessible to those knowledgeable with deep learning. At their core is differentiable programming, and popular implementations are written with Python and PyTorch. This not only opens 3D to the broader machine learning community, but also means there’s significant expertise in the geospatial world to apply and adapt NeRFs and Gaussian splatting

NeRFs and Gaussian splatting connect with technological trends. Drones are becoming widespread, photometric and LiDAR data from cell phones is excellent, VR/AR devices are advancing, and 3D is becoming common in geospatial. There will be a lot of innovation at the intersection of these technologies.

3D replicas have applications in storytelling and accessing spatial data. They effectively convey a sense of ‘being there’. This can be used as an interface to underlying data pertinent to a real world space: access the data by navigating through the 3D world and select the relevant component.

If this subject interests you, or you have any comments or questions, I’d love to hear from you. You can contact me on LinkedIn, Twitter/X, or at ckoziol@gmail.com.