Large Language Models and Geospatial

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are at the center of a lot of conversations currently. I’m particularly interested in how they will impact the world of geospatial. The aim of this post is to think through some of the ideas I’ve had regarding those impacts. Due to a combination of slow writing and a fast moving field, it’s also a tour of some neat proof-of-concepts.

The key ideas are how LLMs can enable:

- Faster access to information through question answering

- Leveraging repositories of text via text comprehension

- Innovative user-interfaces

Although LLMs are often thought of a singular tool, they offer several capabilities. These include vector embeddings, text summarization, logical reasoning, computation, knowledge recall, natural language input/output, writing code, and interfacing with other tools. Differentiating between the capabilities is important since their performance can vary, and because LLMs are likely to deployed within larger workflows.

My overall perspective is that LLMs will be useful components in a geospatial solutions. However, domain expertise will remain relevant, as will deeply understanding the problem you’re solving for the end-user.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) in the Geospatial Context

Extracting relevant information from documents has traditionally been a complex task, particularly if the data is unstructured. LLMs can help identify information efficiently in documents, as well as be leveraged for text-comprehension. Two premises guide my thinking about NLP use-cases in the geospatial context.

The first is that documents have significant amounts of useful data. Geospatial information is not exclusively encapsulated in vector and raster data, but also in texts, plots, and charts. The latter contains analysis, qualitative information, and insights outside that of traditional GIS data. The relationship between information and location may exist in metadata, be embedded in the document, or may be in the context of the information we extract. Examples of files we may want to assess include building assessments, climate documents such as the IPCC Assessment Reports, and regulatory filings related to natural resource estimates.

The second is that for many geospatial related tasks, information extraction requires a high level of factuality, without being exacting. Use-cases of LLMs can be characterized by how strict the requirements on the output are. On one end of the spectrum is creative use cases such as copywriting, text editing, and ideation, where there are many possible good outputs. The other end of the spectrum is occupied by fields such as Law and Medicine, where it’s mission critical that any LLM output can be guaranteed to complete and accurate, due to the severity of consequences. My hypothesis is that geospatial sits close to the Law/Medicine end of the spectrum, yet with slightly more tolerance for mistakes.

Faster Access to Information Through Question Answering

LLMs can be used to accelerate extracting information from documents via chat interfaces. Using the interface, you can ask questions using natural language, and receive an answer derived from the documents, as well as citations and the source text. In this use-case we are not relying on the LLM to have memorized or seen the information previously. Rather, we are searching for the most relevant passages of the documents to the query, and then having the LLM synthesize the answer from those passages. A key assumption is that the relevant information can be found in a limited number of relatively short passages of text. Since the system doesn’t rely on the LLM to generate the facts, it is more robust against LLMs responding with imaginary information.

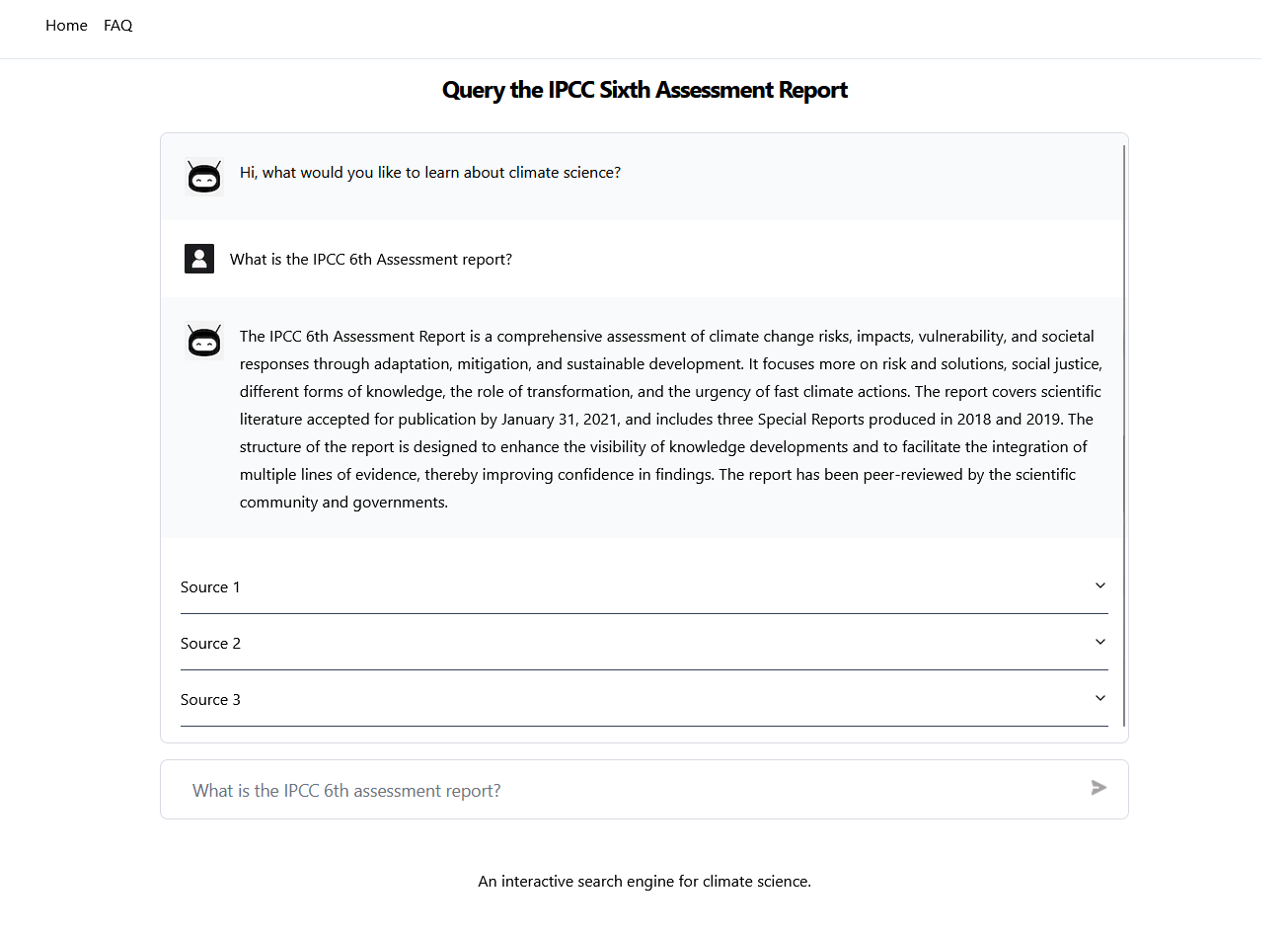

This approach can be leveraged for different structures of documents. One end-member is a limited number of documents containing extensive information pertinent to many locations or phenomena. An example is the IPCC 6th assessment report, which details different aspects of climate change in 10000 plus pages. A chat-interface with documents such as the IPCC report can help identify the impact of climate change on a specific region, limitations of various models by geography, or how spatial distribution of phenomena may change over different scenarios. A proof-of-concept of this application is the site Climate Query I built, which allows you you search for information in the IPCC 6th assessment report. Similar sites: Chat IPCC and Climate Q&A were developed independently.

On the other end of the spectrum we can have numerous documents, each specific to a location. Several jurisdictions require mineral exploration companies to provide assessment reports for their properties on a regular basis. This creates a corpus of documents associated with a specific property and time period of activity. One possibility for a chat-interface is to filter sites based on characteristics such as the geology, characteristics of rock samples, or the types of geoscientific data collected over the property.

Although search, data synthesis, and chat interfaces have been available before — a key part of the innovation is how simple they are to build. Using LLMs we have a flexible algorithm for conversation, formulating answers from multiple text sources, and for creating vector embeddings for semantic search. Open source code for creating question-answering systems exist and are relatively easy to stand up (at least for a demo). Microsoft, which has partnered with OpenAI, offers this capability on its cloud platform Azure.

Automatic search can be intertwined with other technologies. Search through a text and automatically plot the results on a map. Search for text and then have the LLM augment the text by formatting it into a specific format or into a style. Search through a text and on pull relevant data from a spatial database. These capabilities are already being developed.

Text Comprehension

A more advanced NLP application is to use LLMs to ‘reason’ about text. The aim being to derive knowledge which may not be explicitly stated in a document. The extent to which this is possible is an active area of research, and it’ll be interesting to know how far LLMs can be pushed in this area.

One application would be to extract information from research literature as its published to contextualize previous numerical projections or model intercomparisons. Building large earth science numerical models (e.g. a climate model) often requires trade-offs in what physical processes to include, and how to implement them. The complexity and computational cost of these models often means that they lag behind the current research frontier of specific processes. LLMs could be applied to provide information on the strengths and limitations of specific model components in light of updates in research. This would have applications in projections of sea level rise, severe weather, and biodiversity loss.

A futuristic application of LLMs in this area would be for uncertainty quantification, building a system analogous to structured expert judgement (SEJ). SEJ is a formal process to elicit and integrate knowledge from a group of experts. The purpose is to capture the knowledge experts have that may not explicitly available in data or reflected in models, often for the purpose of forecasting. It’s particularly relevant for problems with high uncertainty or limited data. The idea would be to recreate expert knowledge by training an LLM on published research literature. A system of these can than be queried as group of experts. For an application of SEJ to projections of the contribution of ice sheets to sea level rise, I would highly recommend this paper.

A different approach that we can take with LLMs is to evaluate documents against a set of criteria. This is particularly useful when we may have numerous sites or assets each described by an independent set of documents. In this case, we can write a set of evaluation metrics which we want to use to identify sites of interest, and use this to classify or rank sites. This can go beyond search in the complexity of the task. For instance a geologist with scientific hypothesis about what makes areas prospective for different target minerals. Analogous use-cases include using supply chain evaluations to inform business continuity plans, or evaluations of strata depreciation reports to inform risk analysis.

Opening up New Possibilities for User-Interfaces

LLMs can be used to create user-interfaces driven by natural-language. This can make tools like GIS simpler by not depending on users to remember how to navigate through all the options. It can also simplify APIs or command line tools, especially in the common case where a user knows the information required, but not the specific syntax. Leveraging natural language interfaces may help shift towards a paradigm where users aren’t required to be experts in a particular program, but rather in declaring the outcomes.

There are numerous ways to reimagine user-interfaces around LLMs. This includes augmenting existing interfaces with a chat-interface, constructing text-input only interfaces, or building a hybrid interface adapting in real-time in response to inputs. LLMs can not only interpret text-inputs, but can also shape the outputs. LLMs can visualize the data on a map, output a plot, or write a response.

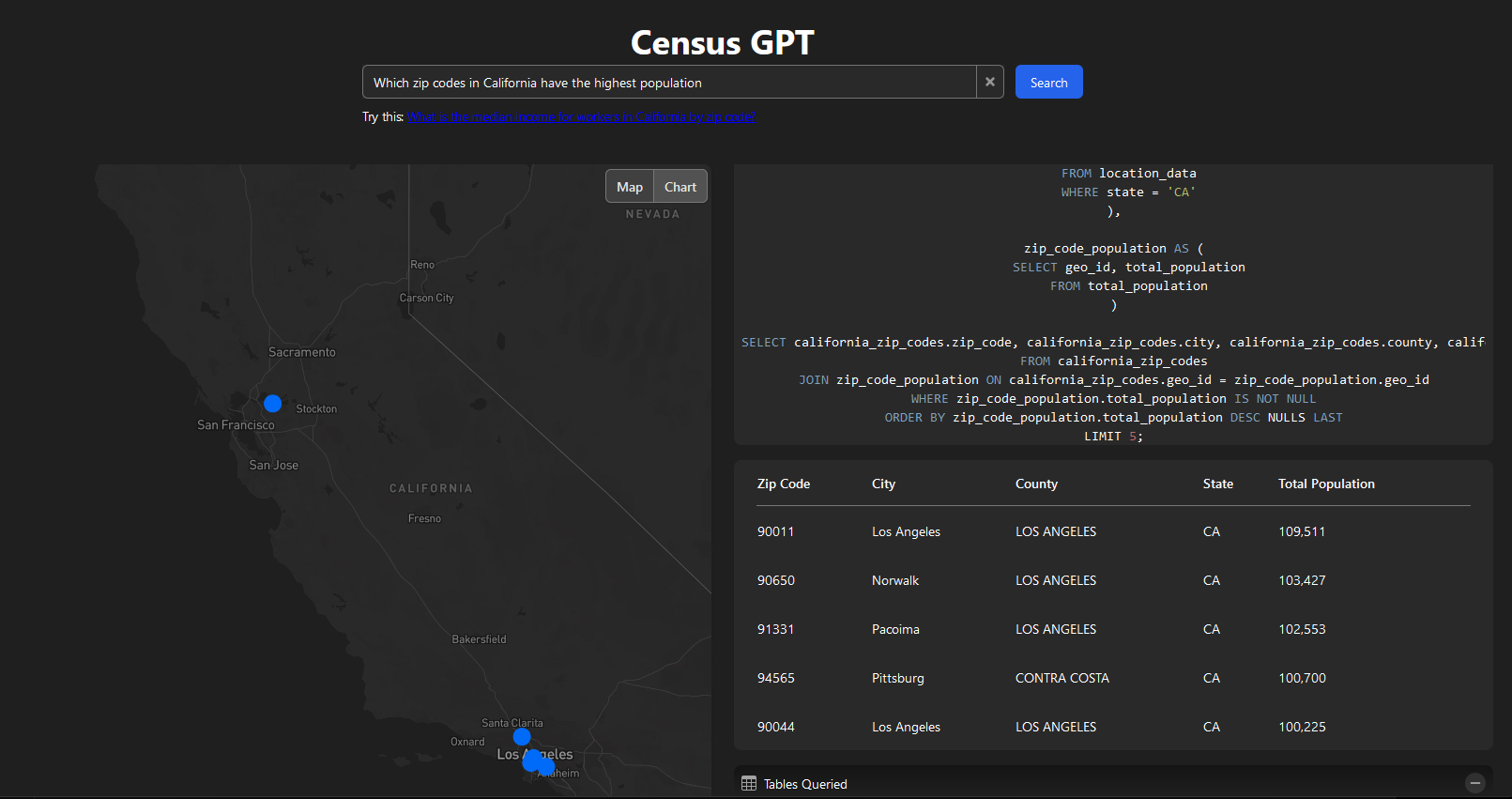

Using LLMs for natural language interfaces in enabled by the fact that they are trained on both natural language and computer programming languages. This means that LLMs can translate a language like English into a computer program like SQL. LLMs can also learn from API documentation, adapt to particular database schemas, and connect to utilities to execute code. These functionalities can be chained together to build a system where a user-input is translated into code, executed, and the output provided in the right format.

Several examples of using ChatGPT in a user-interface have been released. This includes demos by corporations including Planet, Microsoft, and Palantir. A combined map and chat system titled Queryable Earth was released by Microsoft and Planet, which answers user queries either in writing or on a map, depending on which is more appropriate. Microsoft Azure Space has a demo showing ChatGPT finding satellite imagery. Taking an apparent position that LLMs will be 100% reliable and not have AI alignment issues, Palantir released a mockup video showing LLMs integrated in software used for battlefield management.

There’s also been significant experimentation in the open-source community, leading to some fascinating geospatial applications. For instance, SatGPT connects ChatGPT with pystac and rasterio to pull Landsat and Sentinal images based on natural language queries. This project allows you to query and visualize features from OpenStreetMap. Leveraging ChatGPT’s capabilites to write SQL, CensusGPT allows you to query data related to crime, demographics, income, education, and population in the USA and plot the results on a map and in charts.

Conclusion

Since ChatGPT was released in November (2022), there’s been significant discussion about LLMs. This includes LLMs’ impact on geospatial, as well as how the geospatial community can deploy LLMs to amplify its own impact. These conversations are important since geospatial links to key issues such as climate change, agriculture, and social development goals.

LLMS have the potential to benefit both geospatial experts as well as end-users of geospatial products. The use-cases of information-retrieval, better text processing, and improved user-interfaces were touched on this post. As more people experiment with LLMs, other creative applications will be discovered.

The precise impact of LLMs won’t be known for a while. They’re under active development in both research and engineering, and we’ve yet to know how far they can be pushed. Experience also shows that that building AI products is a hard task. Zero to proof of concept is one step, but going to production requires confronting difficult problems such as accuracy, reliability, and consistency.