Can Diffusion Models imagine Natural Disasters?

Natural disasters impact the built environment. In this post I look at whether we can use the latest generative models to imagine the consequences of flooding, fire, and earthquakes on a specific location.

Diffusion models are the latest AI model used for image generation. The outputs are impressive, despite the idiosyncrasies. With the models being open source and accessible, I wanted to explore generating images myself. Previously I’ve played around with OpenAI’s DALL-E model and found that it’s outputs ranged from quirky to dystopian when prompted with terms around climate change. I wasn’t able to elicit much of interest from DALL-E 2 with the same approach, and initial tests with stable-diffusion fell flat. So I went with natural disasters – a topical subject given the heat dome and flooding in British Columbia last year, as well as the COP27 summit coinciding with thinking about this project.

In this post we’ll explore the outputs of RunwayML’s stable diffusion with prompts related to flooding, fire, and earthquakes. It’s important to note that the model hasn’t been trained to produce photorealistic images, nor is intended to reproduce real-life events. The aim is to explore some of the capabilities of the model. Imposing natural disasters onto our current built environment is an approach used for climate-change awareness communication. Artwork around Vancouver displays the height of future sea levels imposed on familiar infrastructure. In addition there’s previous work developing the model ClimateGAN, which leverages a different AI approach with the explicit goal of photo-realistic outputs of flooding.

There’s a few ways we can leverage diffusion models to generate inputs.

- Using only a text prompt

- Using a text prompt, an image, and a mask, where the model fills the masked area

- Using a text prompt and an image as a starting point

- Fine-tuning the model to recognize an object, and then including that object in a text prompt

We’ll go through these sequentially.

Baseline Model

Let’s start by creating baseline images of each of these natural disasters. As the unfortunate subject of the disaster, we’ll use a suburban house. The following three images were created using Stable diffusion with the prompt “House in suburbs, impacted by an <<event>>, streetlevel view, 4k photorealistic, image in the new york times”, where we use the words earthquake, flooding, and fire in place of <<event>>. Finding the best prompt requires some trial and error with the qualifiers to append. The model doesn’t take much time to generate images, so the results were picked from a suite of model outputs.

My first impression is that results are in the right ballpark. The elements you would expect are there, and framing of the image looks appropriate, and the colours have a quality of photorealism. There is a sense of uncanny valley looking at the image, but flaws are inevitable given the purpose and development of the model. Having generated numerous outputs, I think the ones of flooding tend to be better quality (although not the one displayed here in particular). One hypothesis is that images of flooding may have lower complexity, as the house and water components are relatively independent of each other. In images related to fires and earthquakes, the disaster is integrated across the entire image.

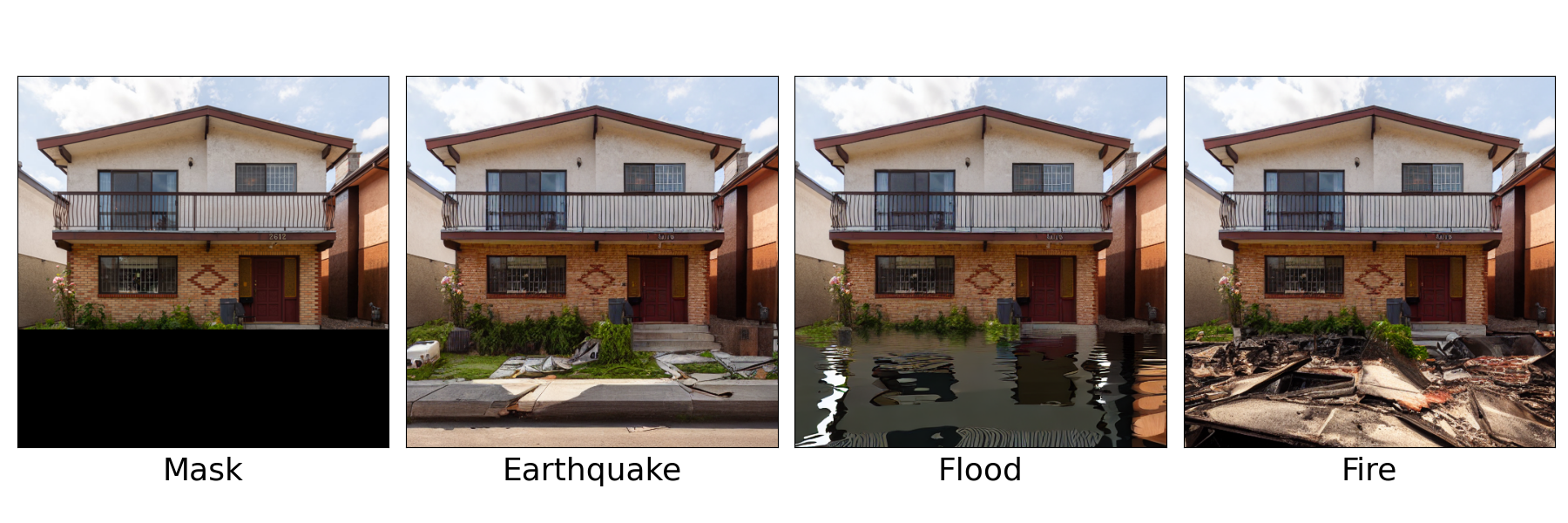

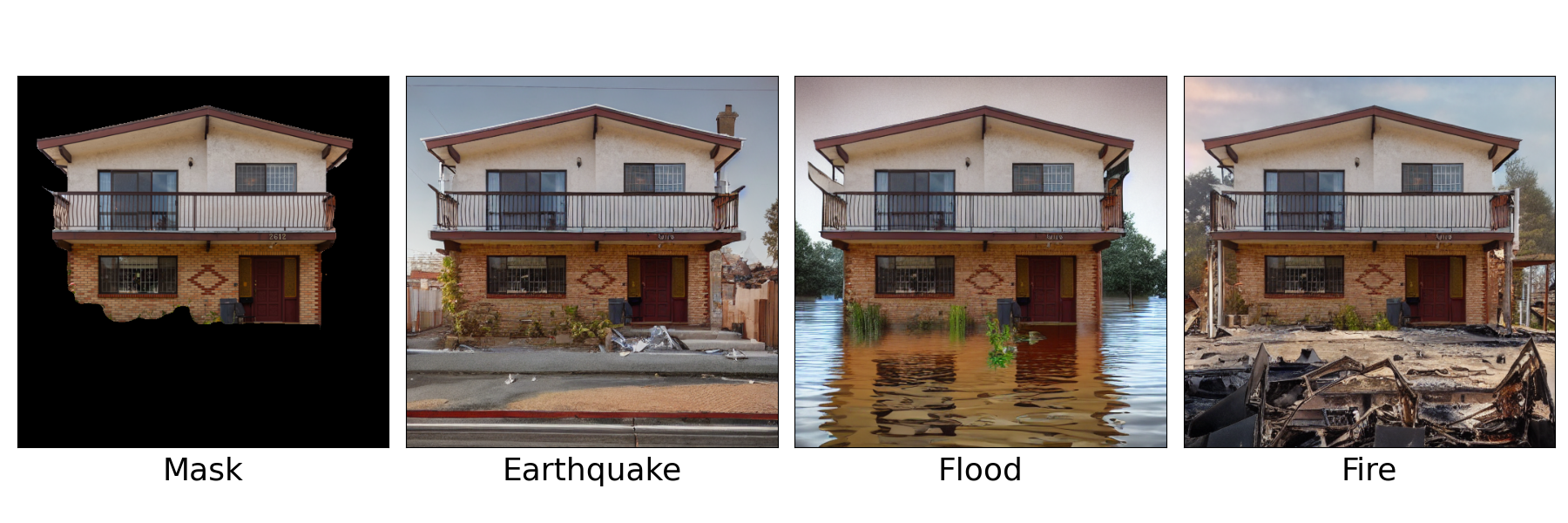

Masking

The second approach we’ll take is to use a mask to update the image with the model. The model will infill the masked area while keeping the remainder of the image untouched. Since you’re limiting the model to generate only part of the image, you’re guaranteed to have the original portion look photorealistic. The trade-off is that the image may appear disjoint. We’ll do this in two ways. The first is by masking the bottom third of the image, and the second is by keeping the house and having the model create everything around it. Masking the bottom third creates images where the disaster looks like it happened in the particular location of the image. Masking the region outside of the house generates images which are more generic, since the house is taken out of context. Here are the results for the first experiment:

Overall the coherence looks good. The image generating earthquake damage is subtle, and I probably wouldn’t have identified it without the label. It looks like the model placed debris in the yard and generated a fractured sidewalk. The interesting aspect of the flooding image is that the model generates reflections in the water. For instance, the door, the window, and the colour of the neighboring house. The flood water is darker than I would’ve expected, and contrasts sharply with the sunny sky. The image of damage from a fire shows the limits of simple masking, since you would expect the house to have damage from smoke. Despite that, I think the model does generate the key idea of the natural disaster. Onto the next set of images:

Whether these images are better probably comes down the use-case. I don’t see much value in the earthquake image, and have a preference for the previous flooding image. This is because the neighboring houses provides the original context, and I don’t see the advantage of the background generated by the model. The image of the house is more striking in the second set of images. The generation of a burnt yard and debris appears more realistic, and the background behind the house has a colour palette more reminiscent of a fire – as if a smoky haze was still present.

Initial Starting Point

Diffusion models work by progressively eliminating noise from images. In the case of our first set of images which were generated using text prompts, the entire image began as pure noise, and through a series of steps evolved into the final images. Rather than initializing the model with pure noise, we can initialize the process with a selected image with noise added. This approach has been quite succesful at turning rudimentary sketches into detailed images resembling the sketch.

I didn’t have much success with this approach. I found the model output typically went one of two ways. The first is that it looked like a corrupted version of the input. The second is that the image looked completely different. It’s possible that I didn’t get the parameters quite right, which is why I get cartoonish results. Here’s one of my outputs:

Fine Tuning

The preceding results were generated using a pretrained neural network with no modifications to the network weights. With fine-tuning, we can update the network with a new object, and then incorporate that specific object into the outputs. For this experiment, I took images of a house, and than ask the model to generate that specific house in the context of the natural disasters. It’s worth noting that I never explicitly provided the model information that the object in the images is a house.

The images I took are shown below. These are taken with my cell phone camera over the course of a few days. To provide the most information to model we want the pictures to be as diverse as possible. I tried to capture the house from different angles, in different weather, and in different lighting conditions. Something on the order of 5-20 images is sufficient to fine-tune the model.

And here are what the results look like:

The essence of the house is generally well captured across the outputs. However, the model does output four instead of three windows on the second floor in some of the images, among other discrepancies.

Mirroring previous results, the flooding and fire images are much more interesting than the earthquake outputs. Part of the reason may be that the model didn’t associate the object in the new images as a house, but as an abstract/generic object. Because of this is doesn’t show a destroyed house as in the baseline. You can see a downed trees in one of the images, but without showing damage to the house itself, it’ll be hard to communicate the notion that an earthquake occurred.

In the flooding images I like that the water colour is not black as in some of the previous results, and that the generated outputs show both night and day. For outputs related to fire, we can see that the fire occurs in the background, and doesn’t impose on the house. Ideally we’d see the fire better integrated into the foreground, at least in some of the images.

Conclusions

Going back to the original question, can diffusion models imagine natural disasters, I think the answer is yes. Could these images be used to convey a photorealistic output? Probably not yet, the deficiencies are still too apparent.

Alongside ongoing improvements to the base model, two routes to improving the outputs are incorporating more images related to natural disasters into the training dataset, and prompt engineering. The first one would need careful ethical considerations on how to collect and process the images. The second focuses on getting better outputs from an existing model by crafting better text prompts to guide the image generation process. As the technology and datasets advance, I don’t think it will be long until generative models might be able to show the consequences of a natural disaster on your neighborhood.